|

| Shutterstock.com |

Ford considers how “toxic masculinity” is shaped from the moment of a boy’s “gender reveal” to her closing chapter, which – simply and powerfully — lists the names of more than 50 famous men who have been publicly accused of sexual assault and their alleged criminal acts.

She traces how gendered inequalities in the way we socialise children at home and via pop culture directly shape harmful adult behaviours. These include “the embrace of online abuse, rape culture, men’s rights baloney and even the freezing out of women from government and leadership”. Ford sets out to demonstrate not only how “toxic male spaces and behaviours … codify male power and dominance” but also how they serve to protect men from any consequences.

In a chapter on domestic labour, A Woman’s Place, Ford shows how gendered division of housework and childcare informs assumptions about adult roles. In a claim that will no doubt be quoted by many “Angry Internet Men” (as Ford refers to them), she proposes that heterosexual women are better placed living alone and inviting men “into our houses as guests occasionally”.

Her point is not that there is no pleasure to be had for a woman cohabiting with a man. Instead she highlights that managing “the gendered conditions of domestic labour … takes a fuckton of work”. This work happens regardless of whether women are consistently fighting for help with washing the dishes or changing nappies, or have begrudgingly accepted that the unending cycle of housework is their burden to shoulder.

Read more: Friday essay: talking, writing and fighting like girls

Short of raising a child in the wilderness, far from an internet connection, television signal or cinema complex, children are inducted into gender norms by the popular culture they consume. In her chapter about Girls of Film, Ford reflects on the experience of a 1980s childhood in which the blockbuster films for young people all required girl viewers to imagine themselves in the place of active male heroes.

Unlike girls, boys are not conditioned to identify with girls and women on screen. This, Ford argues, results in the marginalisation of stories about girls, which “are considered niche and peripheral, in the same way stories about people of colour or stories about disability or queerness are”.

We only have to look to the dramatic online overreaction to the news of a female-lead Ghostbusters reboot, which resulted in the stars of the film receiving sexist and racist abuse. This suggests that many men’s inability to see value in “stories about anything other than themselves” is entwined with the devaluation of women themselves.

|

| Clementine Ford |

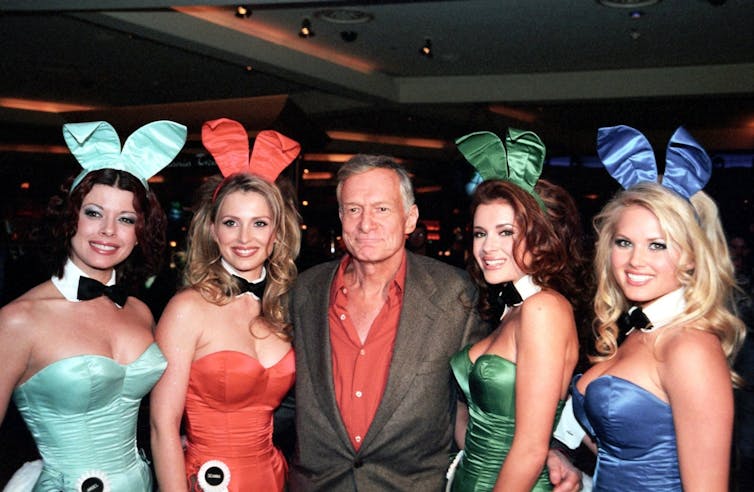

Inevitably, Ford must consider the men who lead these online crusades against the imagined oppression of men. She devotes significant attention to Milo Yiannopoulos, who has become a figurehead of the men’s rights movement. When Leslie Jones, the African-American actress who starred in Ghostbusters, shared some of the abuse she received at the hands of Yiannopoulos and his followers, he accused her of “playing the victim”.

And yet, as Ford identifies, Yiannopoulos resorted to framing himself as a victim when his Twitter account was removed in 2016. In a telling assessment, Ford argues that these men are not united in their “iron-clad fortitude but by extreme fragility, and this is what bonds them together beneath men like Yiannopoulous”.

Read more: #MeToo is not enough: it has yet to shift the power imbalances that would bring about gender equality

One of the most frustrating modern retorts to any attempt to discuss gendered violence, discrimination and outright sexism is that “#NotAllMen” are responsible for these acts and attitudes. However, as Ford cuttingly observes, women do not need a directive to “look for the goodness in men, because we try our damnedest to find it every day”.

Women already know that not all men are guilty of the brutal sexual assaults, for instance, that Ford details in her interrogation of rape culture. The difference for women is that “we know that any man could be [a threat]”. The magnitude of living with such a gendered power imbalance impacts every woman’s thoughts and movements.

While Ford writes with great humour about the abuse she has received and anti-feminist rhetoric more generally, the overwhelming gravity of a world overcome by toxic masculinity permeates this book.

Margaret Atwood’s famous comment that men are afraid that women will laugh at them, while women are afraid that men will kill them, is no more painfully examined than in discussion of the brutal rape and murder of Aboriginal woman Lynette Daley. One of the killers, in his explanation of events to police, stated: “These things happen … girls will be girls, boys will be boys.”

As Ford rallies us to understand, being a boy need not pose a danger to women nor encompass the harms that patriarchy enacts on men, such as increased risk of suicide or the impact of violence.

With an epilogue comprised of a loving letter to her young son, Ford asks us to imagine a different definition of boyhood, in which being sensitive, soft, kind, gentle, respectful, accountable, expressive, loving and nurturing are no longer framed as incompatible with being a man.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.