|

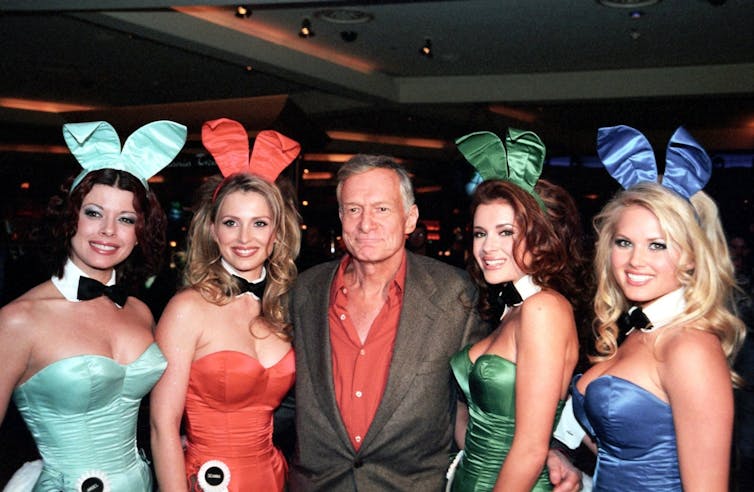

| Hugh Hefner in 2001with Playboy ‘bunnies’. EPA/Glenn Pinkerton/LVNB |

The most surprising detail to emerge after Hefner’s death was that Brooke Shields had featured in a Playboy publication called Sugar and Spice when aged only 10 years old in 1975. Photographer Gary Grosse received $450 to take the photographs of the heavily made-up Shields posing naked in a bathtub. The Sugar and Spice series of books in which the images appeared promised “surprising and sensuous images of women” from contemporary photographers, coding them as “artistic”.

The ongoing controversy about the images, particularly once Shields was old enough to realise that she did not want them in the public domain, affected Grosse’s career as a fashion photographer and he eventually became a dog trainer. Yet the fallout from the exploitative images did not significantly tarnish the Playboy name or Hugh Hefner. Shields featured on the cover of Playboy in 1986 at age 21.

Today in the United States it is a felony in most jurisdictions to publish a nude photograph of a model aged under 18. However, laws about publishing images of minors were not as definitive historically and internationally, particularly if a model’s parent gave consent.

As the internet has become ubiquitous, we have become much more aware of the existence of child pornography and of the paedophiles who seek it out. Viewing and trading sexual images of children is not only a criminal act, but one of the most widely reviled behaviours possible. But pornography and popular culture have often exploited the line between girls and woman with the fetishisation of girls or women who look young.

Pornographic magazines and video have often used the trope of “barely legal” to present young women who are dressed and styled like schoolgirls, often in suburban bedrooms or school settings. As US historian Hanne Blank wrote in 2008, the depiction of “cheerleaders, students, babysitters and sorority girls” in this type of porn means that “the immaturity symbolism is insistent”.

While clearly most people are at the peak of their physical attractiveness in their youth, the fetishisation of young boys for a heterosexual female audience is nowhere near as common as the obsession with young girls within culture aimed at older men.

One obvious reason for this difference is the historic value that has been placed on female virginity in a way that it is not for men. This includes older ideas about the importance of a virginal bride for ensuring that all of her children were legitimate, to more recent notions of women with sexual experience being “sluts” or dirty.

Today the vast majority of people in countries such as the United States and Australia have sex prior to marriage. This could be one reason why girls continue to be sexually fetishised, as they symbolise an innocence and purity that most young women are no longer seen to represent.

While some community groups contend that sexualised images of girls might support the behaviours and actions of paedophiles, there is a more pervasive issue at stake here for all women. One of the legacies of Hefner’s Playboy empire and the sex culture it helped to propagate is that only very young women are sexually attractive. The oldest “Playmate” (the women who feature in the magazine’s centrefold) to have ever appeared in Playboy was 35. Few women aged in their 30s were ever featured.

Conversely, at least nine minors, aged 16 and 17 at the time of photographing, have featured in American and international editions of Playboy. In 1958 Hefner was brought before a court after publishing images of 16-year-old Elizabeth Ann Roberts in a feature entitled “Schoolmate Playmate”. Roberts was described as a “bouncy teenager” occupied by “reading and writing and ’rithmetic”, but she looks physically tiny and vulnerable in the images. The charges were ultimately dropped as Roberts’ mother had consented to the shoot.

While they are not generally focused on depicting naked bodies, women’s magazines regularly name men aged in their 40s and 50s, such as Johnny Depp and George Clooney, as among the most sexually desirable men. One of the legacies of Playboy is its contribution to the fetishisation of young women and a porn culture that toys with the depiction of women who are styled to look as if they are school-aged or just over the most minimal line of cultural acceptability (barely legal).

This article was originally published on The Conversation.