|

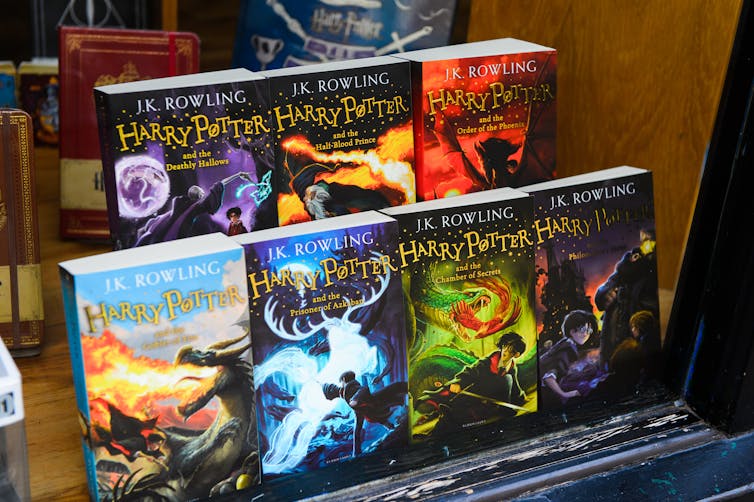

| The Harry Potter series on display in Windsor, England. Anton Invanov/ Shutterstock. |

Last week’s Wheeler Centre event Harry Who? The True Heroes of Hogwarts brought together writers, comedians and musicians to celebrate the series. While Harry and his broken glasses predominate at most Potter tourist sites and film screenings, Harry Who? asked the audience to consider who really is the true hero of J.K. Rowling’s stories.

As readers contemplate the long-term legacy of the Potter universe and whether it will endure, it’s also important to consider the overarching messages of Rowling’s series as the most popular example of children’s literature to date.

Harry embodies the key characteristic of some of the most memorable protagonists of classic children’s literature. From centuries-old stories of Cinderella onwards, child and youth characters who are orphans not only foster the reader’s empathy, but are also freed from the expectations and restrictions that biological parents impose.

Melanie A. Kimball explains the twin effects of child orphans in literature:

Orphans are at once pitiable and noble. They are a manifestation of loneliness, but they also represent the possibility for humans to reinvent themselves.Without the tragedy of Harry’s parents being violently killed by the evil Lord Voldemort, Harry would have had no compulsion to go beyond the “typical” experience of a child with a witch and a wizard for parents.

At Harry Who?, writer Ben Pobjie pointed out that Harry is not exceptional, but that it is his nemesis, Voldemort, who propels Harry to importance. With reference to his dubious celebrity, Pobjie joked that if Voldemort was in Australia, he would “be on Sunrise every morning”. As with the importance of Harry’s lack of parental influence and constraint, the extreme adversity of being Voldemort’s inadvertent nemesis establishes a heroic scenario for Harry to inhabit.

One of the repeated claims throughout the event was that Harry is not much of a hero at all, particularly as he relies on other people to succeed. In the first book of the series especially, Hermione Granger possesses most of the personal attributes and knowledge required to defeat the ever-present threat posed by Voldemort. She is clearly the most intelligent of the Harry, Ron and Hermione trio, and works hard where her male counterparts often attempt to shirk the effort required.

|

| Hermione (Emma Watson) takes the lead in a scene in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004). Warner Bros |

A 2011 study of twentieth-century children’s books found that, on average, in each year, no more than a third of children’s books featured central characters who were adult women or female animals. In contrast, adult men and male animals usually featured in 100 per cent of children’s books.

Though the Harry Potter series does depict some strong and beloved female characters including Professor Minerva McGonagall, it is reflective of an era in which protagonists in children’s literature are usually male unless a book is specifically marketed at a girl readership. In addition, the series is also lacking in the depiction of queer characters, regardless of J.K. Rowling’s post-book declaration that Hogwarts’ headmaster Professor Albus Dumbledore is gay.

With the rapid changes in attitudes toward social and cultural issues including same-sex marriage and children with non-normative gender and sexual identities, the Harry Potter series — as a product of the 1990s and early 2000s – might not endure as well as some might imagine.

|

| Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (1997). Bloomsbury Publishing/Goodreads |

One crucial part of the Harry Potter legacy, however, is its effectiveness in encouraging readers, viewers, and now theatre goers with Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, to embrace fantastic stories about young people once again.

Adults in the late 19th and early 20th centuries delighted in children’s stories and made up a significant segment of the audience for plays such as Peter Pan. The dual audience of children’s literature, for both adults and children, was once the norm and one that did not bring any shame or embarrassment with it.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.